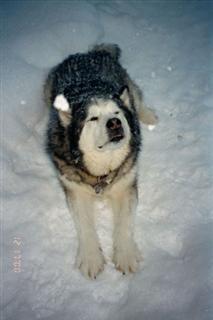

by Zinta AistarsThe Fate of Homeless Animals in Kalamazoo. Published in February 2003 issue of Encore magazine. (Photo of Suni catching snowflakes, see sidebars below.)

by Zinta AistarsThe Fate of Homeless Animals in Kalamazoo. Published in February 2003 issue of Encore magazine. (Photo of Suni catching snowflakes, see sidebars below.)A din of howls, yelps, barks, whines, and soulful meows rises around me as I enter the room lined with steel cages. In several narrow rooms along a hallway in the Kalamazoo County Animal Shelter, over a hundred cages hold strays – dogs, cats, but at times more exotic animals, including snakes, hamsters, peacocks, or even livestock. Most of these strays are picked up throughout the greater Kalamazoo area. Some are brought in by their owners, no longer willing or able to give them a home. Others are removed from an abusive or neglectful environment. Still others are brought in because of a situation endangering themselves or other animals or humans. For almost all of these animals, death by injection awaits them in but a matter of days.

As I pass the cages, cat paws protrude as if to tap me on the shoulder. “Please look at me, please see me, please save me, please take me home with you.” Dogs of every color, shape, size, breed or mixed, watch my every step. Some watch in silence. Some bark at me. Others don’t look up at all. They curl in tight, miserable huddles at the backs of their cages, seemingly resigned to doom. I wonder: do they smell impending death? Do they know?

On Lake Street, just down the road from the Kalamazoo County Jail, the Kalamazoo County Animal Shelter houses approximately 6,000 animals per year. Only about 1,000 of these animals will find new homes. Another 1,000 are “redeemed” by their original owners in happy reunions. For most animals, however, this is the last stop before they are euthanized. Their only hope is a kind-hearted soul moved by their plight and willing to adopt them. For those who are brought in because of biting other animals or a human, there is no such hope. Their fate is sealed.

Val Gearhart, senior administrator assistant director at the Shelter, says: “We take in all strays, as long as they are from the greater Kalamazooarea. No animal is refused. Our hope is that they will be reunited with their owners or adopted by new ones, but unfortunately, most are not. We have discussed the possibility of becoming a no-kill shelter, but lack of funding at this time prohibits that.”

If an animal wears a tag or a license, Val says, the Shelter will call the number on the tag, or trace the license to the animal’s owner and contact them. Each animal brought in is also scanned for a microchip, a tiny device imbedded just beneath the skin that identifies the animal with a code that computer records can trace back to an owner. “We don’t find too many of these,” Val says, “as it is a relatively new way of tagging pets. But there are some, and the chips not only identify the owners of the animal, but also provide medical information.”

Every day, a veterinarian comes in to the Shelter to check new arrivals. Every animal is given a rabies shot, tested for worms, its general health evaluated. Injuries, if any, are treated. Costs for the medical treatments and shots are covered by the Kalamazoo Humane Society – and their funding in great part comes from donations, while funding for the Shelter comes from the County budget, as the Shelter is considered part of the County’s law enforcement agencies. Other financial needs are met through capital improvement funds. A small part of the Shelter’s income comes from fees paid for licensing pets, or fines incurred by a failure to purchase a license or other fees or fines associated with animal ownership. Adoption fees for dogs housed at the Shelter are $35 (including $5 for a license), $30 for cats. For animals not yet spayed or neutered, a fee must also be paid, the amount dependent on the new owner’s veterinarian of choice.

“Because of our emphasis on spaying and neutering animals,” Val says, “we are beginning to see a slight decrease in numbers of dogs brought to the Shelter. We like to think these are the results of encouraging pet owners to keep their animals from breeding indiscriminately. Even so, come spring, the Shelter is often full to capacity with both dog and cat litters. Puppies and kittens are usually adopted more quickly than adult animals, but too many must be destroyed for lack of a home.”

With a close collaboration with the Kalamazoo Humane Society (KHS), the Shelter refers to KHS those potential pet owners who wish to adopt, but lack the funds for spaying or neutering their pet. “Operation Fix-It” through KHS performs these procedures for minimal fees for owners who are able to show financial need.

“Pet population control is still one of the greatest problems,” Val says. A lack of understanding all that pet ownership involves, she continues, is another. Too often people buy pets, whether from a shelter or a pet shop, without fully considering all that owning a pet requires. “Someone interested in adopting a pet must first plan for owning that animal. They must have the budget for the care and maintenance of their pet. They should consider the size of the animal in terms of the living space they can offer it, and whether they have children or other pets, how the new pet will interact with the rest of the family. It’s important to think ahead about how a pet will fit into one’s lifestyle. A pet needs care and attention just as a child does. At least once a month, a new pet owner returns an animal to the Shelter because they failed to plan.”

A dog the size of a Saint Bernard but pure white in its coloring watches us as we pause by his cage. He is beautiful, his eyes bright with intelligence, his gaze sad with, it seems, an understanding of his fate. Val explains that the dog was brought in by his owner, who no longer was able or desired to care for the dog. Perhaps he, too, was an impulse buy – an irresistible bundle of cute puppy, growing into an animal rivaling a toy pony in size, outgrowing his owner’s ability or desire to care for him. Planning means considering not only the “cuteness factor” of a puppy or kitten, but also what they will become as a fully-grown animal.

“Most of us love our pets as we love any member of our family,” Val says. “But we see our share of abused and neglected animals, too. I traveled for several days with one of our animal control officers to see what they have to deal with answering calls that come in to our dispatchers. Most calls are complaints from neighbors, calling to report a dog barking, or running loose. We receive calls to report injured animals. But we also receive calls reporting animal cruelty. In many such cases we simply talk to the owners and do our best to ensure the situation is corrected, but in some circumstances, if we see that the animal is in distress, we will remove them.”

When the call is to report something like an animal left outside in the cold, or, in the summertime, reporting a dog locked inside a car and becoming dangerously overheated, the animal control officer attempts to educate the owner about more appropriate pet care. If the animal is in distress, however, because of beatings, starvation, or other abuse, steps can be taken to remove the animal in hopes of finding a better home.

“Many people have a view of the animal control officer as a ‘bad guy’ who picks up strays and has them put to sleep,” Val says. “But our officers do everything possible to help animals in distress, return lost pets to their owners, and rescue injured animals, bringing them in for medical care. It’s fair to say that pretty much every person who works at the Kalamazoo County Animal Shelter owns at least one pet that they adopted from the Shelter. Many of us own several pets that we found while working here. I have a dog and two cats at home, too,” Val smiles. “My children fell in love with a kitten brought into the Shelter with a deformed paw. After daily exercise and massage, Xander grew up to be a normal, healthy cat. We all wish we could do more…”

Burnout, she says, is a real problem for those who work at the Shelter. It can be difficult to work with the animals, feeding them, keeping their cages clean, caring for them, but then having to watch so many of them euthanized because no one has chosen to adopt them. After all efforts are made to either reunite pets with their owners or to find new and loving homes for them, most will never leave the Shelter alive. A veterinarian comes in daily to put animals to “sleep” if they have not been adopted after a period of seven days, sometimes longer if space allows.

“Aldonis Mezsets is one of our volunteers who comes in regularly to film animals up for adoption,” Val says. “Every week he prepares a new video of cats and dogs available for adoption. The video, called ‘Doggie in the Window,’ is aired on community access channel 21 every day from 10:30 a.m.to noon. It’s only one way of our trying to let people know about the animals we have here. We are also currently working on a web site that we hope to have up and running in the early months of 2003, providing information about our services, but also posting photos of the many wonderful animals we have here waiting for someone to love them."

As Val and I stand talking, an orange and white cat limps over to us. Quasi is one of the strays that was brought into the Shelter but not adopted. With a crippled paw, no one was interested in taking the cat home, but the staff took pity on the cat and made her a pet of the Shelter. She twines and brushes around our ankles, purrs contentedly when I squat to scratch her white chin. Quasi is one of the lucky ones. Barbie, a gray cat, is the other Shelter pet, a sixteen-year-old feline who sleeps on her pillow and moves about slowly, showing her years.

Val says: “We try not to show favoritism, and we try not to grow too attached to the animals here, but sometimes it is impossible. Most of us work here because we care about animals, and we hope we can help them to live long and happy, healthy lives. Nothing makes us happier than to hand over a new pet to a loving home, or to reunite a lost animal with its family. We work with a network of other organizations whenever possible to help the animals. When we receive calls about wildlife, we might contact area zoos or rescue groups to care for these animals. We give talks at area high schools about responsible pet ownership and volunteer opportunities. We educate pet owners about how to treat animals properly. If we are too often left with no alternative but to euthanize animals, it is because their owners have been irresponsible about their care and maintenance, or because people allow their animals to breed indiscriminately, or because no one has adopted the animal.”

The Kalamazoo County Animal Shelter, along with director Ann Marie Kreuzer and assistant director Val Gearhart, employs seven animal control officers deputized through the county sheriff’s department, three office staff persons, two full-time and one part-time kennel staff persons, and many volunteers. Volunteers are trained at the Kalamazoo Humane Society.

“While we can always use more volunteers,” Val says, “we can especially use donations to the Shelter. Cash donations are appreciated, of course, but we also accept dog and cat food, both canned and dry, treats for puppies, carpet pieces, old towels and blankets for bedding, bleach and detergent to use for cleaning cages. If anyone has an interest in making a donation, in adopting a pet, or in general information, we’ll be happy to answer any questions.”

Quasi limps into a corner and settles in to give herself a wash. The din of howls and meows quiets for a moment as the few visitors to the Shelter disperse. A young woman, cuddling a kitten under the warmth of her sweater, leaves the hallway of cages to complete paperwork at the front desk for the kitten’s adoption. This one has been chosen to live. The others remain, waiting.

For more information, call 269-383-8775.

Foster Homes Provide Alternative to EuthanasiaAcross town from the Kalamazoo County Animal Shelter, in a small store in Maple Hill Mall, is the headquarters for Kalamazoo Animal Rescue. Much like the Kalamazoo County Animal Shelter (KAR), they work to rescue cats and dogs from cases of abuse and neglect. Unlike the Shelter, the animals they rescue are never euthanized.

An all volunteer, non-profit organization founded in 1991 and funded solely by private donations and fund raising events, KAR functions in great part through the help of a network of volunteer foster homes for homeless animals awaiting adoption. Paula Lewis, one of approximately 90 volunteers currently working for KAR, rushes into the store with a bouncy beagle in tow. The beagle, happy over the outing and sniffing his surroundings curiously, perks up at the approach of a small child, hand outstretched. Could this be the one? Could this be… the hand that leads to home?

“We have about 35 foster homes in operation now,” Paula says, watching child and beagle in fascination with each other. “Mine among them. But we can always use more!”

Volunteers mill about the store, busy selling an array of tee shirts, mugs, and pet supplies. Like the foster homes for the animals, the store is temporary space. KAR’s lease is running out in early 2003, and they will need to find a new place, but in the interim, the network of foster homes and volunteers will continue.

On this evening at the KAR store, there appear to be many more human faces than animal faces. That, says Lisa Reeber, president of KAR, is the norm. Animals are normally to be found where they are most comfortable, in their foster homes, but they are brought in to the store on designated days to be viewed by the public, or they are taken to area pet stores to be seen, and hopefully adopted, by passersby. Volunteers also take available animals to radio and television stations to promote them and KAR.

Lisa explains: “Our goal is to provide animals the highest standard of care while seeking permanent homes for them. This not only includes housing and all the love and tenderness that goes along with living in a home instead of a steel cage, but also full veterinary care. All of our animals, without exception, are spayed or neutered prior to adoption.”

“We have turned away people, but we rarely turn away an animal,” Giti Henrie says. She is a volunteer at KAR, like everyone else, but also a board member. “All animals are taken in unless we have a shortage of homes, but if an animal is injured, it is given highest priority in placement. People, however, are a different story. We do not allow just anyone to adopt a pet. There are no on-the-spot adoptions; every potential owner is interviewed. We take time to talk with each person who wishes to adopt an animal, and we discuss living arrangements, the needs of both owner and pet, and we explore the level of commitment a person is willing to offer a pet. A pet is not something to be acquired on impulse. That pet will be a part of your family for maybe 15 or so years – that’s a long term commitment.”

With 150 to 200 phone calls coming in to KAR each month, the need for more volunteers and more fundraisers seems neverending. Julie Hirt is marketing coordinator for KAR, and she eagerly directs interested parties to KAR’s newsletter, “Rescue News”, and the informative web site – www.kalamazooanimalrescue.org – that informs all who are interested about this alternative to bringing strays to the Kalamazoo County Animal Shelter. The site offers extensive information about the organization, features and photographs of available animals, hints on animal care, applications for volunteers, lists of needed volunteer services and donations, and news about upcoming events, including the popular “Fur Ball.”

“Since the inception of KAR,” Julie says, “we’ve placed around 3,000 animals in loving homes. We want people to know that there is an alternative to euthanasia for unwanted animals. We had a dog live in a foster home for seven years before it was finally adopted. Every animal deserves a good home. Here, there is no deadline to finding one.”

Kalamazoo Animal Rescue can be reached at 269.349.2325.

Dancing Puppy Paws on a Kitchen FloorLying back on my couch, I reached for the remote control, ready to enjoy an hour of relaxation at the end of a long workday. A bad habit, I suppose – I can’t resist constant channel surfing. But this time, my button caught on a channel. This was no movie, no colorful entertainment show. Channel 21 was showing what appeared to be a home video of a parade of animals. Someone was walking a dog across the television screen, urging the Alaskan Malamute to turn towards the camera. He was huge. He was gorgeous. I leaned in towards the television screen. The great face turned towards me, intelligent brown eyes seeming to meet mine, the handsome face resembling a wolf. The camera panned with him as he walked a few more steps. He was dragging his hind legs a bit. The limp was almost imperceptible, but it was there. His face turned towards the camera again. I was in love.

Suni – a version of the Latvian word “sunis” meaning dog – became mine a few days later. My two cats were skeptical about his arrival in our home, but Suni was, for all his size and power, as gentle as a teddy bear, allowing my tomcat, Tommy, to bat him across the nose a few times in greeting, and Jiggy, my black calico, to hiss at him her catty disapproval. It wasn’t long, however, before Suni became guardian of “his” two cats, and protected them, as well as the human members of his new family, against any danger or irritant that might cross our paths. He was a gentle soul, deeply affectionate, and I never doubted that he understood that he had been saved from euthanasia by a matter of days. The intelligence in his eyes told me he understood everything – and he was grateful.

Five years later, when Suni’s life was over, and brain seizures forced a heartrending decision to have him put to sleep, I held his handsome head in my arms as he drew his final breath and wept as one does when losing a cherished member of the family. I grieve for him still.

With the passage of time and a healing of heart, I returned again to the Kalamazoo County Animal Shelter. The loss of Suni left my home with a void only a dog could fill. Walking up and down the aisles, I peered into each steel cage. The din of desperate howls and meows was breaking my heart. If only I had room for more than one… Which to choose? Which one? I looked into each pair of eyes, searching for the connection. There was a plea in each pair. I said a silent prayer for each animal soul. All living beasts deserve to be loved. A young Chow mix stuck a damp nose between the bars and gave a soft whine. He was smaller than a full-blooded Chow, but his tongue, which is black in the Chow breed, was a spotted pink and black, showing his mix. His fur was matted and dirty. I asked a staff member if I could take the golden dog, his fur tinted just beneath with black, for a walk up and down the hall. I was given a leash, the cage was opened, and the dog bounded out with joy. Freedom! He hardly knew how to suppress his joy. Scampering up and down the hallway, he finally settled up against my knees. He seemed to think he belonged with me. Who was I to argue?

Some might say this was a lucky day for Guinnez. A reprieve. I say – lucky me. A house is not a home without the sound of dancing puppy paws on a kitchen floor.