Kalamazoo College alumni magazine

|

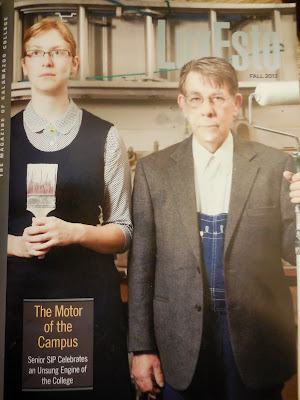

| Stephen Mohney (Photo by Daina Bowman) |

Connections to Ghana

by Zinta Aistars

|

| LuxEsto Fall 2013 Issue |

In Ghana he’s Kwesi,

the southern Ghanaian name for a boy born on Sunday. Although sometimes when

children see Stephen Mohney '76 walk by, they shout “Kwesi obruni.” That, Mohney smiles, means 'white guy born on Sunday,’

a name affectionately applied to every white man after the introduction of

Christianity. In Ghana, in the villages of Wli and Hotopo, Mohney is a

recognized man.

And a welcome sight. He brings with him the gift of a

gateway. Mohney is the co-founder (with Donald Yao Molato) of Tech4Ghana, a nonprofit organization that

builds computer centers and libraries in Ghana, promoting rural development and

education.

Mohney, however, is not in Ghana on the day I meet him. He

is in Public School 3, in the historic Bedford Village neighborhood of

Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, New York. He is walking the hallways, and as he

passes, teachers greet him, children grin at him, and through the open door of

a classroom in session, a group of children brush their fingers beneath their

chins in an open-fingered wave at him.

"That's the Spanky-and-the-Gang wave from Little Rascals," Mohney whispers.

He stands in the classroom door for a moment and brushes his fingers under his

chin back at the smiling children.

"I've been teaching here for 27 years," Mohney

says. "At this point, I teach children of parents who were my students,

and it's the parents who give me that Spanky wave. They remember!

"The Bedford Village School is the oldest school in

continuing operation in New York City," he adds, pointing to one of many

displays he has created around the school. One display showcases the school's

history, dating back to 1721. The school became a New York City public school

in 1891, and integration began in the early 1900s. "By 1947, the

graduating class was all black," Mohney says, "and the community

experienced the flight of the whites, and many of the brownstones you see

around us were cut up into small apartments. In recent year, the community is

experiencing ‘gentrification.’"

Today, the school educates 634 children, kindergarten to

fifth grade. The principal, Kristina Beecher, in her fifteenth year leading the

school, was once a student at P.S. 3. When Mohney walks into her office, her

smile widens.

"I don't know what I would do without him,"

Beecher smiles, and the admiration is mutual. The two banter a bit, but quickly

move into discussion of the school's current problems. The population is

dropping, and there's uncomfortable talk going around about closing P.S. 3 and

replacing it with a charter school.

"Last year we were told to eliminate the arts,"

Mohney's forehead pulls into hard lines. "Arts have long been a draw to

this school. And we had to cut music. Can you tell I'm not a fan of charter

schools? Our school sign states it takes a village to raise a child, but it

also takes a child to raise up a village. Charter schools get more money, but

that doesn't make them better schools. We don't get rid of our children when

they misbehave, but we get the kids when the charters kick them out. Why would

you not fix every school for every child?"

From the principal's office, Mohney continues his walk up

and down the hallways, where children move by him in orderly lines, some

holding hands.

"Education has just gotten harder over the years,"

Mohney says. "We're up against a lot. There's a lack of parenting skills,

kids are learning to solve problems with violence—" He stops. "I'm on

my soapbox again, aren't I? I guess that dates back to my years at K. Ah, those

radical 70s, when I was an anti-war conscientious objector with long hair. Art

teachers aren't superfluous! They teach literacy with their art. They teach

children how to express themselves."

Mohney's cheeks flush again, but his smile never wanes, at

least not for long. He shows off the classroom at P.S. 3 where a visual arts

teacher has snuck in elements of social studies to teach from his own travels

to Morocco and Turkey. In the cafeteria, a science teacher has incorporated art

into teaching about nutrition—the walls are lined with paintings and collages

of colorful vegetable people. The school blossoms with color and the rebellion

of art sustained.

|

| Interviewing Stephen for this story in New York |

Then, down another hallway, a long section of the wall is

draped with the vibrant, patterned fabric of Africa. It is a student-created cloth

similar to "kente," woven by the Ewe and the Asante people of Ghana. Part

of the fabric is in the cool colors of blues and purples, used by the Ewe

people. The kente of the Asante blazes in oranges, reds and gold.

Mohney stops. It’s a crossroads of sorts, where one home

touches on another home. Staff and faculty at P.S. 3 know well about his work

in Ghana. More than a few are donors to Tech4Ghana, and a couple have traveled

there with him during summers. Passion like his is contagious. Picking a corner

room where all is quiet, he settles in to talk about his other home.

|

| LuxEsto pages |

The story starts on August 13, 2009, with the opening of a

computer center in Wli, Ghana. Actually, it starts long before that. Mohney was

a kid, sizing up colleges. West Africa was on his mind, and he was looking for

a college that could send him there. He had spent a couple years in Kenya when

his parents taught school in that country.

"Kalamazoo College was my first choice, but it was too

expensive," Mohney says. "When I didn't respond to the acceptance

letter, I got a call. I didn't know about the financial aid available, and when

I was offered aid, I did accept.

"When I first arrived at K, I thought I would major in sociology

and anthropology. Then I took two African history classes from Dr. William

(Bill) Pruitt, who I came to consider my mentor. And I soon made the decision

to take as many classes as I could from [Professor of Religion] John Spencer. I

was intellectually challenged and disciplined in his courses. I ended up as a

religion major, not because I was that interested in religion, but because I

was interested in learning all that I could from Dr. Spencer."

Connections with fellow students were as memorable as those

with professors, and one in particular would become very important.

|

| Stephen and Case talk over Skype |

Though his memory is a bit foggy on the precise timing, Mohney

crossed paths with Case Kuehn ’74 through mutual friends during his freshman

year. "I'm not sure when I met Casey," Mohney ponders, "maybe in

the summer of '74, before my study abroad experience in Ghana, when I was in

the College singers, and, as a music major, he directed us." Even before their

respective graduations, the two lost touch. And with one living in New York and

the other in Seattle, chances of a reunion seemed unlikely.

Then, not long ago,Kuehn found himself musing about finding

a good cause to support. Paging through old College yearbooks, browsing through

the pages of LinkedIn.com to check on old friends, Kuehn came across Mohney—and

wondered what he was up to all these many years later.

The friends reconnected online. One thing led to another,

and, after 40 years, Ghana would become their virtual meeting point.

As Mohney sits in a

room at P.S. 3 in New York, Kuehn pulls up a chair to his desk in Seattle, and

both boot up their laptops. With the help of Skype, images pop up on their

laptops. This will be the first time they’ve seen each other in four decades.

"So that's what you look like!" Kuehn gives a

whoop.

Mohney laughs. "That's me."

Last time they saw each other, Kuehn grins, his hair was

shoulder length and curly and his chin bearded, but Mohney's long blond locks

dangled somewhere near his elbows.

Today, Kuehn is CFO of Loud

Technologies, one of the world's largest professional audio and music

products companies. "Stephen and I have complementary skill sets,"

Kuehn says over Skype. "When I was feeling that I needed to do something

beyond my sphere, and I tracked him down on LinkedIn and read about Tech4Ghana,

I thought I might be able to help."

Kuehn had his own African connection, having spent time in

Zambia as member of a music group. "The fact that Tech4Ghana was so

grassroots appealed to me. After I contacted Stephen we began e-mailing daily. Tech4Ghana struck me as something tangible that I could be involved in, and I

knew my contacts, my experience, and the legal services to which I have access

could all be beneficial."

Mohney adds: "I jumped at the opportunity to work with

Casey. Aside from my own funds, his was one of just a few donations I received,

and now we have submitted the paperwork to become a 501(c)3 corporation. That

will make all donations tax-deductible.

"When I travel to Ghana, I usually take along six or

seven laptops," Mohney says, "but with the funding that Casey is helping

us obtain, our goal is to bring 35 to 40 laptops along each trip. We take our

ability to communicate worldwide for granted here. At the Tech4Ghana computer

center, people come in longing to see and touch the computers. In Ghana, many

students must learn computer skills by textbook only, without access to any

computers. I showed one of these teachers a jump drive, and he had never seen how

such a thing actually works. I saw another teacher break out into a sweat; he

was so excited to be able to touch a computer. In 2011 we opened up Wli’s

library there."

Stories about the Tech4Ghana enrich the two friends’

conversations. Kuehn looks forward to a future trip to Ghana to see the library

and computer center for himself.

"Another issue we are working to address is gender

equity," says Mohney. "The computer center draws boys and adult males,

and some of them stay for hours, practicing and learning. Children come in to

look at the donated books or to play games on the computers while learning computer

skills. But the girls want to learn, too."

Girls in Ghana, Mohney says, have far more responsibilities

at home, and education is not seen as a priority for females. Mohney has

observed teen mothers, babies on their back, walking by the computer center

slowly, looking in. He and Kuehn are brainstorming about ways to increase

access for girls and women, perhaps even bringing laptops to their homes.

This desire to increase computer and library access to both

genders is shared by other Tech4Ghana team members. Kofi Anaman, a Ghanaian-American

who lives in New York, and his wife, Susan Ewurasi Anaman, a teacher at P.S. 3,

and their daughter, Adjoa, are deeply involved with the organization.

"If we want to prosper economically and socially,”

Anaman says, "we can't leave the girls and women behind."

Anaman and Mohney met in Ghana 25 years ago. Anaman had just

completed junior college, and was doing his obligatory year of national

service. "Stephen was in Ghana to film videos to educate children,” says

Anaman, "and a year later I was able to come to the United States to help

him with the videos."

|

| LuxEsto pages |

Children in New York, Anaman says, need to see how children

in Ghana live. In Ghana’s urban areas children experience skyscrapers and

modern amenities—but life in rural Ghana is quite different. Education, he

says, can make an immeasurable difference in these areas. Anaman brings his

daughter along on his visits back home, because it is important to him that she

experience the cultural differences and be aware of the privilege she enjoys.

"Stephen is a very giving person," Anaman says,

"and he would give his last penny. Even a little goes a long way in Ghana.

Stephen gives money, but also his knowledge and his time. He understands the

importance of education; he was more thrilled than I was when I earned my

master's degree here in global business and finance. I credit that in great

part to Stephen."

The library that Tech4Ghana is building in Hotopo will honor

Anaman's father, who lacked college education himself, but held firmly to its

importance for his own children.

Tech4Ghana’s co-founder and co-director in Ghana is Donald

Yao Molato, who serves as the organization’s eyes and ears and hands on site,

keeping the computer center and library running smoothly, and designing and

supervising the expansion of the educational campus.

|

| LuxEsto pages |

Last summer Tech4Ghana hosted its first Kalamazoo College intern,

Gift Mutare ’14, an international student from Zimbabwe. Mohney glows with

satisfaction at how the puzzle pieces have been falling into place.

"I want to do more and replicate the work to the next

community, and then the next,” says Mohney, “until we've truly bridged the

digital divide and offered opportunities for many more people and addressed the

gender bias in Ghana.

"When Casey

showed up and then committed himself to help, I knew I was in good company and that,

together, we could do this."

One day some 40 years ago Mohney sat in a Kalamazoo College

classroom, taking notes and listening closely to his professor and mentor, Dr.

Pruitt. On that particular day his professor had invited a guest speaker to

class, Kofi Awoonor, a writer and professor (SUNY Stony Brook) and years later

Ghana’s ambassador to the United Nations. Mohney was mesmerized. At the end of

the class they met, and Awoonor pointed a finger at Mohney—fresh from study

abroad in Ghana, brimming with his unforgettable experiences. "Now," Awoonor

said. "What are you going to do for Ghana?"

No comments:

Post a Comment