The last time I had walked into the building that was now known as The Occupation Museum in Rīga, it was a very different museum—a museum of lies. It was on my first trip to then Soviet Latvia, and we traveled as a tour group (something I never do, preferring to travel alone—but the Soviet government did not allow solitary travelers, as it would be too difficult to keep an eye on all of us). Our group gathered in the lobby of Hotel Riga, the only hotel in which “foreigners” were allowed to stay, and we were carefully sheparded by a Soviet tour guide onto a bus, over to the museum, off the bus, and in a tightly gathered group through the museum. It was the mid 1970s, and the walls of the museum were plastered with paintings of Soviet workers, fists upraised, holding sickles and hammers, all in glory to Joseph Stalin and Vladimir Lenin.

|

| Concentration camp barracks |

Attendance at the museum was obligatory.

All these years, I did not return to the museum. Not even after Latvia had regained its independence, and the museum contents had been tossed into the garbage heap, to be replaced by what was for Latvians very much like the Holocaust Museum in Washington D.C. I couldn’t bear to go inside. My stomach churned and retched at mere sight of the heavy, brown building on the shores of the Daugava River.

|

| Latvian flag |

My fears were abated the moment I went inside. No one was watching me as I walked in. No one was examining my face for my response. No one was leaning in to hear my conversation with Alda. No one was pushing me along from exhibit to exhibit, filling my brain with mush. I could move about freely, at my own pace, and come to my own conclusions.

I had been to the Holocaust Museum in D.C. This was smaller, but it was very similar. Similar barracks replicated, similar human stories of suffering. Families torn apart, starvation, torture, execution, a wave of refugees, battles waged in the streets, the cities and villages, and finally in the forests as guerilla warfare, in a wave of resistance to the Soviet government that lasted, amazingly, into the 1960s.

|

| Latvian refugees escaping the country in boats, my family among them |

It was almost too much. Yet we were drawn to see, to understand, to know. This was our history, too. We looked at documents, old passports, military orders, refugee belongings, old weaponry, copies of government pacts, photographs, diaries, letters, newspapers. A large photo showed the three men, rulers of superpowers, tossing the Baltic States like poker chips in a game of human lives… and the chips went to Joseph Stalin. He sat grinning his victory, next to Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Winston Churchill, to whom, apparently, we were nothing more than a nuisance to their greater plans.

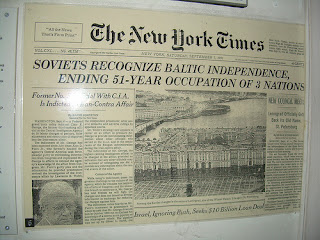

To the credit of the United States, despite Roosevelt’s betrayal, the Baltic States were never acknowledged by this government as being legally a part of the Soviet Union. Go figure. But better late than never … 51 years later, we were acknowledged again as a free nation, and the first to accept our new and independent government was Iceland.

|

| Weapons used in Latvian resistance movement |

Sunlight dazed us as we emerged again from the museum. It had been a very different experience, indeed, than the time before. I knew this history … I knew it from my family, from school, from my own later reading and research. I knew it from hearing Andris’ stories, giving me another level of understanding when I heard about life in Soviet Latvia from my own counterpart, my own generation, realizing, there but for the grace of God go I… I knew it, but to see the artifacts with my own eyes was sobering.

Calling us out of our dark reverie was yet another golden day. After such a morning, we craved sunlight and beauty, and Alda and I headed toward the center of the city, to Bastejkalns park. After all, my mother had told me such stories, too, of warm days in the park, long walks arm-in-arm with first crushes, of sliding down snowy hills on toboggans, and of walking along the Riga Canal to school. She had lived in the northern section of Riga, on Ropažu Iela, and had gone to school in the city. Her route to school took her directly through the park.

Bastejkalns was one of my favorite spots in Rīga. The city had, in fact, many parks, and flower vendors on most every street corner attested to the Latvian love of nature. A dose of green was a necessary part of every day, and perhaps even more so because life had been so dark so long, flowers in all their gaudy glory were everywhere. Boats floated lazily down the canal, oaks and maples and willows and linden trees leaned branches over the water, graceful stone sculptures popped up in the middle of flowerbeds, ducks paddled over its mirrored surface, and people strolled and sat on benches, taking a moment out of their day to connect with nature.

In a world that sometimes reeled in insanity, in the brutality and cruelty of man against man, nation against nation, these patches of beauty brought sense back where there was none. Yet again, I was struck by how color had returned to Latvia. From these years of gray—gray buildings, gray faces, gray lives—to this vibrant color, almost frivolous, yet in essence, deeply necessary.

(To be continued…)

No comments:

Post a Comment